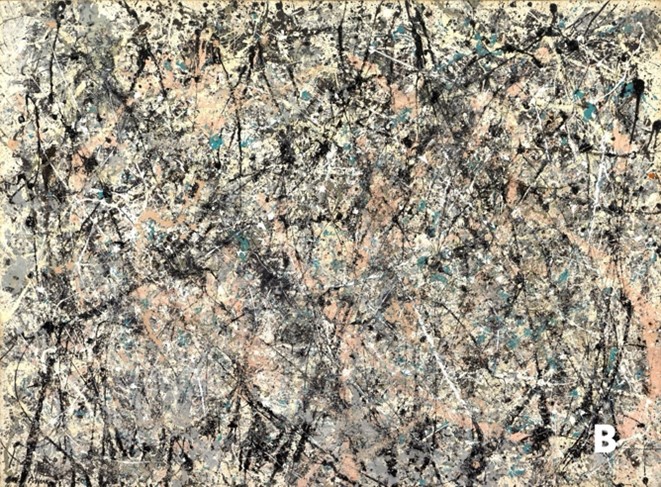

One of these images below is a Jackson Pollock painting and the other is AI-generated – can you spot the difference? The answer will be shared at the end of this bite. This raises an intriguing question: What does it mean to be creative in an era when AI can instantly generate a unique business logo, an Emily Dickinson poem, or an abstract expressionist artwork that is virtually indistinguishable from the original style?

Source: National Gallery of Art

Recent research from University of Pittsburgh scholars highlights the difficulty of responding to this question and offers a perspective on how to move forward. AI is already quite profoundly changing our understanding of creativity and artistic value. Edouard Machery and Brian Porter, Pitt scholars in the History and Philosophy of Science Department, asked AI to generate a series of poems in the style of well-known English-language poets including Geoffrey Chaucer, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickenson, and Sylvia Plath. These were presented alongside the poets’ originals to over 1000 study participants. Judged by this non-expert audience, AI-generated poetry was found indistinguishable from human-written poems. Even despite this, participants were systematically more likely to rate the quality of the AI poems higher than the human ones. These findings were published in Nature in November 2024.

This is a huge shift from existing discourse on AI in the arts. Critics have traditionally claimed that AI is incapable of producing work that emulates emotional depth and complexity. It is this kind of emotional capacity that feeds into creativity and abstract thinking—traits we often think of as distinctly human. But AI can now imitate human-produced creative outputs to a standard that humans themselves cannot distinguish.

Before we concede “art is dead… AI won… humans lost”, perhaps a more optimistic approach is on hand. Pitt Assistant Professor Morgan Frank collaborated on a Science paper published in June 2023 offers ways to consider AI in creative spaces along aesthetic, legal, and labor axes. Alongside colleagues at the MIT Media Lab, Morgan argues that AI should not be deemed “the harbinger of art’s demise, but rather a new medium with its own distinct affordances.” In other words, rather than viewing AI art as a replacement for human skill, perhaps AI technologies can be positioned as another location in which to have genuine and ongoing conversations about creativity, originality, and imitation.

I think this is a good time to remember that imitation has long occupied space in creative education. Many elementary and high school students will remember diligently painting tiny brushstrokes to mimic the Broken Color technique of Monet’s Waterlilies or picking through the syllables of sentences to find an iambic pentameter that mirrors those from Shakespeare’s plays. Indeed, imitation in the service of Western arts education dates back to the first century BCE and remained central to the arts education throughout the Renaissance. Students are still encouraged to “copy the Masters” by producing studies of famous works from throughout the Western artistic tradition because imitation is a way to learn, and to develop the skills needed to branch off into individualized creative pursuits.

What I suggest is that, rather than marking the end of human creative pursuits, the integration of AI may be the beginning of a new era of creativity and reflexive imitation. What can we learn from AI closely imitating human poetry about human-generated art? How might this change the values we use to judge artistic work? This would not be without its challenges, setbacks, and faults. But perhaps integrating AI is the next iteration of an exceptionally long tradition of imitation in the arts -- a jumping off point for developing further creativity and conversation.

Answer: A is AI generated.